Note: This article was originally written in 2019, and has been recently updated to reflect current events and trends. Any updated information within the article was done by our fact-checker, Fawn.

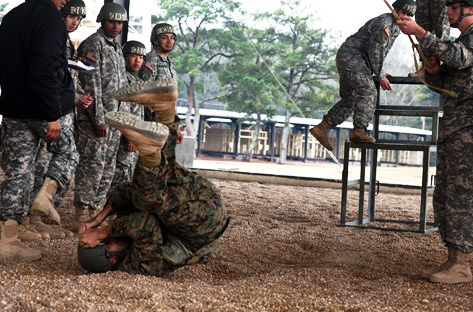

Jump To A Section

Where is Airborne School?

In the counties surrounding the Chattahoochee River, the natural border between Georgia and Alabama, lies Fort Benning, the training grounds for the US Army’s infantry.

Established in 1917, Fort Benning is built upon a site originally used by the Dawson Artillery, a Confederate unit during the Civil War.

Fort Benning takes up 287 square miles and is home to about 35,000 military and civilian personnel.

In addition to schools for the infantry, as well as Ranger School, Sniper School, and many other specialized courses, Fort Benning might be best known as the home of the US Military’s Basic Jump School, aka Airborne School.

Related Article – List Of Army Bases In The US

Airborne School Requirements

Because everyone in an Airborne Division is supposed to be Airborne qualified, just about every MOS can sign up to get into Airborne School.

The minimum requirements are as follows:

- Age: Must be less than 36 years old on the date of application.

- Medical: Pass a Standards Of Medical Fitness Exam (AR 40-501)

- Physical Fitness: Take the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) and pass with a score of 60 or better in each event in the 17 – 21-year-old category.

- FAH Test: Successfully execute a flexed arm hang (FAH) for a minimum of 20 seconds

- Enlisted personnel: Must have successfully completed Basic Combat Training, OSUT, or other service equivalent training

- Officer personnel: Must have completed either Cadet Basic Training for West Point cadets, or under scholarship / contracted for ROTC cadets

1. Airborne Medical Exam

A new recruit qualifies for Airborne School via a medical examination known as the Airborne Physical.

Every recruit, Airborne candidate or not, goes through something similar when they first enlist in the Army.

It’s just that the Airborne Physical is held to slightly higher standards, seeing as how the recruits’ bodies will need to withstand the impact of jumping at high altitudes.

Related Article – Army MOS List: A List Of All 159 Army Jobs

The exam is similar to a normal Army medical checkup, with additional things like:

- Eyesight Test: Distinguish between red and green

- Height and weight check

- General health questions: Do you have vertigo/motion sickness / etc.

- Orthopedic checkup: Here they’re basically checking to make sure you’re fully mobile and that you don’t have any chronic pain issues

The medical exam takes place before the recruit goes through Basic Training, and it isn’t anything to worry about.

(Fair warning #1: the exam does involve a doctor, a rubber glove, and a genuine lack of bedside manners.)

2. Pass The Army Combat Fitness Test (17 – 21 yr. old standards)

In addition to the medical exam, all Airborne School applicants must pass the Army’s Combat Fitness Test.

Known as the ACFT, this 6-event test measures a candidate’s physical strength and ability, as well as their overall cardio fitness.

Related Article – Green Berets Vs. Army Rangers: 5 Major Differences

If you’re already in the Army, you know what this test involves.

For those civilians out there, the test is done in this order:

-

- 3 Reps Maximum Deadlight

- Standing Power Throw

- Hand-Release Pushup

- Sprint Drag Carry

- Forearm Plank

- 2-Mile Run

You must complete all six events within 70 minutes.

To qualify for Airborne School, candidates must complete this test with a min. score of 60 points per event.

Keep in mind that this is based on the standards for those 17 – 21 years old.

Essentially what this means is, even if you are 35 years old (the maximum age for Airborne School), you still need to score as if you were 17 – 21 years old.

Here are the minimum scoring requirements:

| Age Group | Gender | 3-Rep Max Dead Lift | Standing Power Throw | Hand-Release Pushup | Sprint Drag Carry | Forearm Plank | 2-Mile Run (min.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 - 21 | Male | 140 | 6.0 meters | 10 | 2:28 | 1:30 | 22:00 |

| Female | 120 | 3.9 meters | 10 | 3:15 | 1:30 | 23:22 |

(Source: army.mil)

Pushing out any more push-ups or a faster run time is just icing on the cake.

Doing better on the test will not increase your chances of going to Airborne School.

In fact, your grader may even stop you from performing any more reps once you hit the minimum standards required.

Related Article – Airborne And Air Delivery Specialist (MOS 0451)

3. Army Basic Training

It should go without saying that successfully completing Basic Training is the main qualification for a recruit before entering Airborne School.

For recruits straight out of infantry training, Airborne School will seem like a vacation.

Although the instructors (referred to as “Sergeant Airborne” and colloquially known as “Black Hats”) take their job very seriously, they are not drill sergeants.

This means they won’t be screaming at you for no apparent reason.

They won’t flip your bed or toss your room if something is slightly out of order.

And they won’t jump at every opportunity to enforce group punishment.

This is because Airborne School is a gentleman’s course, and it really is meant to teach a skill, rather than break down a civilian and carve them into a mean, green, fighting machine.

When do I sign up for Airborne School?

A new recruit signs up for Airborne School at MEPS—Military Entrance Processing Stations—which officially marks day zero for the soldier-to-be.

MEPS is also where a recruit signs a contract, partakes in medical examinations (such as the Airborne physical), takes a drug test, takes the ASVAB, and swears in front of the American flag to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States from all enemies, foreign and domestic.”

In short, MEPS is one of the longest and most boring days a recruit will endure.

However, a recruit should do his or her best to cherish it, as it is one of the last days they will enjoy civilian clothes and the freedom to slouch for at least a few months.

Current active-duty soldiers who want to go to Airborne School need to request through normal channels. Those already assigned to airborne units should contact their G1 and submit an A1 application through ATRRS.

To request reassignment to an airborne unit, you’ll need to submit a volunteer packet to your branch for approval.

Related Article – How To Join The US Army

What Should I Bring?

If you’re attending Airborne School, you should consider the following packing list:

- Your own blankets and pillows

- Canteen (Pick up one at the PX for $6)

- Extension cord and power strip

- Wet wipes

- Headphones

- Playstation or other game consoles

Everything else that you absolutely need will be provided to you, but click here to see some other items to consider.

Some Things That You Need To Bring

The only required items that you are supposed to have is your ID card and your ID tags.

You also need to have clear Ipro safety glasses, as well as a strap to keep them on your head.

Since you’re not allowed to wear contacts at Airborne School, you need to have the correct eyeglasses to wear behind your Ipro safety glasses.

You also need a PC, or Patrol Cap. If you have a rank, it needs to actually be sewn onto the cap itself.

If your rank is not sewn on the cap, you won’t be able to wear it.

Your patrol cap is the only headgear you will wear, other than your Kevlar helmet.

You will also need 4 uniforms, 4 PT uniforms, as well as civilian clothing for your weekend bar excursions.

Also, bring plain white or black socks (no logos), and they need to cover the ankles.

You’ll also need 5 pairs of cushion-soled socks, either black or green.

Related Article – Delta Force (SFOD-D): Selection, Training, Motto, and More

One of the more important things you need to bring to Airborne School is two pairs of hot-weather tan boots. They must meet the official uniform requirements.

This is often one of the most overlooked things most guys forget to bring.

They should be lightweight, but good enough to run in.

Also, make sure they have solid ankle support. You’ll need it on your jumps!

Speaking of footwear, you’ll also need a good pair of PT shoes since you’ll be doing a lot of running.

You don’t need an expensive pair of Air Jordans, either.

They’re going to get destroyed at Airborne School, so no need to spend $300 on a pair of sneakers.

Just pick up a cheap pair of brand running shoes like Asics Gel-Venture 5 or Under Armour Assert 6 if you’re looking for an inexpensive but comfortable brand.

If you’re heading to Airborne School during the winter months, you should also make sure you bring some warm clothing.

Army-issued Silkies aren’t gonna do anything to keep you warm, and even the waffles won’t do much in the biting cold.

On top of that, during harness week you’ll have to take all of that stuff off.

Related Article – Air Force Pararescue (PJ’s): Career Details

You need to be thinking about bringing a solid type of fleece jacket that you can put on over your shirt and under your blouse.

You should also bring a combination lock.

Notice I said a “combination lock”, and not just a simple padlock.

You won’t be able to carry around a key with you all day during training, and there’s a good chance you might lose it during a jump or some other training evolution.

It’s imperative that you bring a combination lock to jump school with you, as there have been reports of theft.

Some Things That You Should Bring

The following are not required items for Airborne School, but it’s a good idea to bring them.

One thing that they don’t tell you is that you actually do NOT make your bed at Airborne School.

Instead, you take all of your belongings like your blankets and pillow, and lock them up in your locker.

So instead of using the uncomfortable Army-issued blankets and pillows, you can and should bring your own.

Another thing that is issued to you at Airborne School is a canteen. The problem is, that same canteen was likely used by about 500 other airborne recruits before you.

Nasty…

Spend the $6 or whatever it is nowadays at the PX and buy yourself a new canteen.

There are not a lot of electrical outlets in the barracks, so everyone will be fighting over them to charge their phones, iPads, whatever.

Bring an extension cord and a power strip and your fellow recruits will love you for it.

Make sure you lock up all of your stuff at the beginning of each training day, though.

If the instructors see any of your gear left out near your bunk, they will give you a counseling statement (a fancy way of saying you’ll get in trouble).

Believe it or not, you should also bring wet wipes. For whatever reason, the Army always seems to have a shortage of toilet paper.

The last place you want to be is on the toilet seat after crapping out that Taco Bell from the night before, only to find that there’s no toilet paper left.

Another thing that you should bring to Airborne School is headphones.

You’ll have a lot of downtime in the barracks, and with a bunch of other dudes there, it can get kind of loud at times.

Don’t get the expensive Dre headphones, as there’s a fair chance they will get stolen.

What You Should NOT Bring

- Supplements: Supplements are completely banned at Airborne School.

- Food: No food is allowed.

- Pets: Seriously, who brings their pets to Airborne School? You’d be surprised…

- Weapons

Airborne School Length

Army Basic Training lasts 10 weeks and AIT— Advanced Individual Training —lasts from four weeks to more than seven months, depending on the recruit’s MOS.

So how long is Airborne School?

Compared to basic training, Airborne School lasts only 3 short weeks, including weekends and (most) evenings off.

Each week of the school corresponds to a phase of training: ground week (week 1), tower week (week 2), and jump week (week 3).

Here’s a detailed description of how each week pans out.

Ground Week (Week 1)

In the first week, an Airborne School recruit can expect to spend a lot of time familiarizing him or herself with:

- The equipment a paratrooper uses

- How to properly put on a parachute rig, and

- Classes on jumping procedures

In this week, you will not complete any actual jumps.

Rather, it’s intended to give you a full understanding of what it’s like to jump out of a perfectly good airplane.

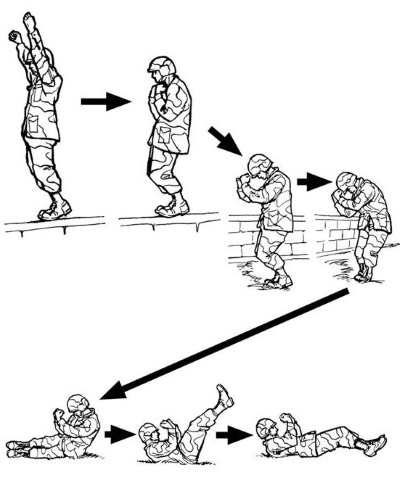

A typical day in ground week consists of morning runs, push-ups, pull-ups, and jumping off a platform in order to learn and perfect the Parachute Landing Fall, or PLF.

The Parachute Landing Fall is exactly what it sounds like: it’s basically a controlled crash into the ground.

You will practice the PLF from a variety of heights, progressively getting higher.

The PLF essentially works out to 5 points of body contact with the ground:

Point 1: Balls of your feet

Point 2: Side of your calf

Point 3: Side of your thigh

Point 4: Side of your hip

Point 5: Side of your back

Here’s a visual demonstration of what it looks like:

You will practice the PLF dozens of times, and your instructors will correct any issues as they see them.

They will be checking for things like proper body positioning, as well as proper landing technique.

Learning this technique is absolutely essential for any paratrooper for one main reason:

You Will Hit The Ground Hard

The parachute used by Airborne (known as the T-11) is not a controllable/steerable parachute.

According to the manufacturer, the T-11 falls at an average descent rate of 18 ft. per second.

Unlike a square ram-air parachute, you will not be able to slow your descent when you get close to the ground.

When you hit the ground, you need to do so in a way to prevent yourself from getting injured.

Your First “Jump”

By the end of week 1, the by-now bruised recruits spend a day learning how to properly exit an aircraft by jumping out of a 34 ft. tower and zip-lining over a sandpit.

The jump out of the tower isn’t a gentle ride.

Before the recruit starts his descent, he will experience a brief free-fall meant to replicate the actual experience of jumping out of a plane.

Keep in mind that this isn’t actually a real jump under a parachute.

You’ll be attached to a zip line, and be completely safe.

Fair warning #2: With that said, do your best to “adjust” the harness straps that run between your legs. You don’t want one of your balls ending up in the ‘wrong’ place, trust me 😉

Tower Week (Week 2)

In week two, AKA tower week, the recruit continues to perfect his or her airplane exiting procedures as well as work on the PLF.

You’ll still be zip-lining out of the 34 ft tower, and you’ll also be introduced to your first real taste of what it’s like to be a paratrooper: mock door training.

Mock door training is exactly what it sounds like; you’ll be lining up and “jumping” out of a mock airplane doorway.

Like the other aspects of Airborne School, it starts with a “crawl, walk, run” mentality.

You’ll start off jumping through a mock door just a few feet off the ground.

After you’ve mastered the basics of exiting an aircraft “on the ground,” you’ll then move on to exiting a mock door higher up.

Throughout this portion of the training, recruits will also be taught another very important part of jumping out of an airplane: emergency procedures.

A lot of things can go wrong when you’re jumping out of an airplane, and everything is exhaustively covered on the ground before you take your first jump.

Some of the more common emergencies that happen when you’re a paratrooper are:

- Total and partial malfunctions of your main chute

- Collisions and Entanglements

- Emergency landings

Chute Malfunctions

Note: The purpose of this is to give you an idea of what to expect at Airborne School, and is NOT intended as a guide. Follow all instructions given by your Airborne instructors!

One thing that you’ll train for very rigorously is partial and total chute malfunctions.

Even though this might be your biggest fear (besides heights), you should keep in mind that main chute malfunctions are extremely rare in Airborne School.

In fact, they are so rare that I couldn’t find one instance where a jumpers main chute and reserve chute didn’t deploy.

With that said, accidents do happen.

You will learn the various recovery procedures for any and all types of chute malfunctions, including:

- Cigarette rolls: A partial malfunction that happens when the chute provides no lift capability.

- Streamers: Also a partial malfunction involving a loss of lift. A streamer malfunction is when a parachute is deployed but fails to inflate properly.

In each of these scenarios, you will conduct what’s known as the pull-drop method.

The pull-drop method is a technique that involves deploying your reserve chute, which all Airborne students will have on.

Collisions And Entanglements

Another emergency procedure you will train for is collisions and entanglements.

These are scenarios that involve colliding with another paratrooper, and/or becoming entangled in their lines or chute.

You will discuss several instances when this can happen, and go over the proper recovery procedures in excruciating detail.

Emergency Landings

As mentioned earlier, the type of parachute used in Airborne School is not the kind that you can steer around.

You’re essentially at the mercy of the wind, and whatever direction the wind is blowing, that’s the direction you’ll be going!

As a result, it’s possible for you to end up drifting down onto things that weren’t originally planned.

There are 3 types of emergency landings that are discussed thoroughly:

- Tree landings

- Wire landings

- Water landings

While they (the Airborne School staff) aren’t going to intentionally drop you over the water, trees, or wires, this is always a possibility in real-world missions.

Throughout week 2 of Airborne School, you’ll be taught exactly what to do in these specific situations.

Ft. Benning 250 Ft. Tower

By the end of the week, the recruit spends a few days jumping off Fort Benning’s famous 250-foot towers.

Even though the recruit should expect to feel really nervous, there really isn’t any reason to worry.

Injuries jumping off the towers are extremely rare. The recruit will be strapped in as well as attached to a parachute.

Try to have fun with it!

Jump Week (Week 3)

Lastly, the third and final week, Jump Week, is when the recruit gets to put all of his or her theory into practice.

It also happens to be the most important week of the course, and the longest.

Throughout this week, you’ll essentially go over everything covered in Weeks 2 and 3, albeit in a much more abbreviated way.

In the roughly hour-long brief, you’ll go over the PLF, emergency procedures, malfunctions training, and how to rig your chutes.

After that, you’ll head on over to pick up your main and reserve chute.

Once you’ve picked up everything you need, you’ll walk back over to the staging area and put on all your gear.

Like most things in the Army, there’s a lot of “hurry up and wait” that goes on in this phase of Airborne School.

So expect to be sitting around a lot.

Since there will be so many of you, you’ll be assigned to a “group” that you will jump with (called a Chalk).

Once your Chalk is called, you will shuffle out to either a C-130 or a C-17 and load up.

Pray that it’s a C-17 because they are a lot more comfortable than a C-130!

So how many jumps do you do in Airborne School?

In order to pass Airborne School, the recruit has to complete 5 jumps, 2 of which will be with a full combat load (a thirty-five-pound rucksack and a weapons case carrying a dummy weapon) and 2 will be “Hollywood,” which means the recruit will be jumping with nothing but a main and reserve parachute.

The last jump the recruit does in Airborne School is a combination combat jump and night jump.

It’ll take place Thursday night, the night before graduation, and the recruit can expect some beautiful and amazing night-sky views.

Is Airborne School Really Difficult?

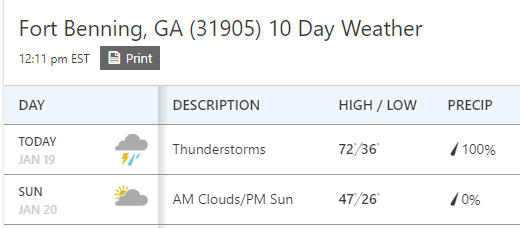

Depending on what time of year a recruit’s airborne class begins, one unexpected challenge in the course may be the long hours exposed to the weather.

Georgia’s heat and humidity are commonly known as brutal forces throughout the country, but most people don’t realize how cold Georgia’s winters can be.

Click Here to read about this author’s time at Army Airborne School.

One day it can be in the low 70s, and the next could be in the mid 40s.

An Airborne recruit won’t have to worry about snow, but in January and February, he or she can expect the temperature to be around freezing, as well as to be standing outside enduring such temperatures for days on end.

Additionally, the recruit will be moving around, building up a sweat, thereby allowing every rest stop to become an opportunity for the recruit’s sweat to freeze over.

In Airborne School, every candidate has to pass the Army’s Combat Fitness Test (ACFT) in the 17-21 years of age bracket, no matter the actual age of the soldier.

For candidates straight out of basic training, passing the test shouldn’t be a problem, as he or she will have just finished spending a few months training for it.

Second to getting injured, the most common way that a soldier fails Airborne School is failing the ACFT.

Come prepared, take the workouts seriously, and anyone should be fine when it comes to passing the physical requirements of Airborne School.

Any special advice or tips?

My personal advice for how to best survive and pass Airborne School comes with the caveat that success or failure isn’t always up to the recruit.

However, here it goes: Don’t Get Hurt.

It goes without saying that jumping out of an airplane is extremely dangerous.

In some cases, there have even been a few deaths at Airborne School. You can read about a few of them in the resources section below (see Airborne School deaths).

It’s extremely rare, but it does happen.

However, most injuries in Airborne School occur during other phases of the training.

Due to the vast amounts of time a recruit spends jumping off platforms, out of towers, and down zip lines, rolled, twisted, or even broken ankles are the most common injuries in the school.

The most common injuries include:

- Physical injuries sustained during routine training

- Injuries sustained from equipment

- Injury sustained from static lines

- Mid-air collisions

- Parachute failure (extremely rare)

- Injuries sustained from landings

You can see an example of “when things go wrong at Airborne School” in the video below:

The instructors will do their best to keep the recruit safe, but accidents like this do happen, so listen closely and pay attention.

If an injury during an actual jump occurs, it probably is the result of an improper PLF. On my last jump in Airborne School, my best friend from basic training landed in a sitting position, cracking his tailbone.

I am not sure what exactly happened, but I do know that he didn’t get to graduate and had to go to a non-airborne unit in Texas and that I never saw him again.

Who CAN go to Airborne School?

Airborne divisions are comprised of just about every MOS, so even if you aren’t set on joining one of the combat arms units—infantry, artillery, and the like—a recruit still has the opportunity to be a paratrooper.

As of 2017, the Army started allowing women to sign up for infantry training, so gender in no way plays a role in who can or cannot go to Airborne School.

Other branches of the military—Navy, Air Force, and the Marines—do send their members to the Army’s Airborne training, but typically on a case-by-case basis.

For example, Airmen looking to become an elite Para-Rescue Jumper will go through Airborne School, as will Marines going to Force Recon training.

If a recruit happens to go through Airborne School in the summer, he or she can expect to be going through the training alongside Army officer cadets, usually, those who are only a year or two away from becoming pinned as second lieutenants.

Who CANNOT go to Airborne School?

The only limitation keeping someone from entering Airborne School is the failure of the Airborne-specific medical exam.

This isn’t something a recruit can train for, and he or she will find out if you are disqualified during MEPS, even before basic training starts.

The exam ensures that a recruit doesn’t suffer from a long list of illnesses and/or diseases, and he or she will likely already be aware of the disqualification long before the exam.

For a complete list of physical limitations, consult the Army manual AR 40-501 here and skip to Chapter 5.

It has a full list of medical limitations for Airborne training, which is too lengthy to post here.

What happens after Airborne School?

New recruits don’t get any say in where they will get stationed, and on that note, I recommend that a new recruit becomes familiar with the saying “to the needs of the Army.”

It is a volunteer service, after all.

If the recruit graduates Airborne School as a regular paratrooper, he or she can be expected to be stationed at one of three US Army Airborne units:

- Fort Bragg in North Carolina as a soldier in the 82nd Airborne (by far the biggest of the three)

- Joint-Base Elmendorf-Richardson in Alaska as a soldier in the 4th Brigade, 25th Infantry Division (where the author of this article was stationed)

- Vicenza, Italy as a soldier in the 173rd Infantry Division (where the author of this article wished he’d been stationed)

Other Potential Assignments After Airborne School

If a recruit is continuing on to more specialized training after Airborne School, such as Ranger Regiment selection, or the selection process for Special Forces training he or she can expect a wide range of bases to be stationed at.

The three Ranger Regiments are at:

- Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia

- Joint-Base Lewis-McChord, Washington

- Fort Benning

As far as Special Forces units, there are five active duty groups and two National Guard groups.

The five active groups are in:

-

- Joint-Base Lewis-McChord, Washington

- Fort Bragg, North Carolina

- Fort Campbell, Kentucky

- Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

- Fort Carson, Colorado

The two National Guard groups are in Draper, Utah, and Birmingham, Alabama.

What happens if I fail?

Like my friend who broke his tailbone on our very last jump, if a recruit fails Airborne School, and he or she is new to the Army, the recruit can expect to get sent to any number of the non-Airborne units around the continental US or worldwide.

Conclusion

If a recruit hasn’t joined the Army yet and he or she is worried about the physical requirements of Airborne School, don’t be—basic training will more than prepare the recruit.

A recruit shouldn’t be turned away from Airborne School simply because he or she is afraid of heights.

Related Article: 41 Questions To Ask A Military Recruiter

I consider myself to be pretty comfortable high up, and I was scared out of my mind every time I jumped.

In other words, scared of heights or not, jumping out of a plane is terrifying and kind of insane.

If a recruit is really gung-ho about being all that he or she can be (a now out-of-date Army motto), they should strive to be more than just a paratrooper.

I encourage recruits to sign up for the Ranger Indoctrination Program (RIP), or, better yet, go straight for Special Forces selection.

I actually recommend RIP rather than SF selection, because one can always progress from a Ranger regiment to SF, though it is much more difficult to go from failing SF selection to RIP, and may not be possible at all.

Airborne operations are not common in modern warfare. In fact, the last major operation happened in the very early years of the Iraq invasion.

As a veteran, I am proud to call myself a paratrooper, but I have to be honest and say that in my four years jumping out of planes (all twenty-plus jumps of mine happening during training exercises) I mostly felt like I was just paying homage to the airborne units of the past: like those soldiers that jumped into Europe and Africa under heavy enemy fire.

Still, I wouldn’t have done anything differently. Airborne all the way!

Resources:

Airborne School Deaths

A Personal Story About Army Airborne School

The writer of this article is a bona fide graduate of Army Airborne School.

Check out his story below:

In the summer of 2008, I was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia. I had just completed sixteen weeks of Basic Training and Infantryman school, and I was five days away from completing Basic Jump School and becoming a US Army Paratrooper.

Me and my fellow soon-to-be-paratroopers had already endured two weeks of grueling heat, breath-stealing humidity, and hundreds of airborne-related drills, but on this day, we were about to perform our first live jump.

A flight manifest was read and, to my surprise, my name was called to be the first soldier out the door. I shuffled up the back ramp of the C-130 prop plane leading the other seventy-or-so airborne students.

Seventy soldiers were on my plane, but there were five planes taking off, so all-in-all there were about three hundred and fifty soldiers in the sky that day.

“Ma’am,” I yelled over the roaring engine, “Are you OK?”

A first lieutenant sat across from me, and when the huge engines turned over I noticed that the lieutenant’s gaze was intensely focused on her boots. We were all terrified, but she looked especially pale.

“Ma’am,” I yelled over the roaring engine, “Are you OK?” She looked up, and the next thing I knew she unzipped the top of her camo blouse and threw up down her shirt.

(For two weeks, we’d been reminded time and time again by the Airborne cadre that whoever throws up in the plane has to scrub down the entire bird.)

Though my stomach turned at the sight of someone puking into their own clothes, I was also in total awe. “Badass, ma’am,” I yelled, and looked towards the front of the plane.

We probably flew for twenty minutes, circling the southern skies, Fort Benning, the city of Columbus, and the Chattahoochee River below. Of course, time was irrelevant. The only thing that was going through my mind was, This is a perfectly good airplane. Why don’t we just land?

“Keep looking at the horizon, Private,”

In my later years as a paratrooper, I came to find out that that exact sentiment—almost those exact words—are commonplace in airborne units. The feeling that a paratrooper experience in the moment leading up to his or her first jump is the definition of pure dread.

Plus, as I mentioned, I was chosen to be the number one man out the door, which made the whole dreaded experience exponentially more terrifying.

A light somewhere above the side hatch that we would be jumping out of was stoplight red when the jumpmaster gave me the command to stand up, hook up, and shuffle to the door.

I unclipped the quick-release device from the carrying handle of my reserve parachute, attached it to the steel cable running north-south through the body of the C-130, and waited for my next command. “Check equipment!”

As the number one man, I didn’t have anyone’s gear to check, but I felt the lieutenant—the one with puke drying in her cammies—run her hand over my main chute, static line, and harness.

The light turned yellow, and the jumpmaster swung a flat-palmed hand towards my face. “Stand by.” On legs that didn’t feel exactly stable, I turned ninety degrees to the right and faced the door.

He rotated the lever and the sound of air rushing by at 120 knots took my dreaded state and multiplied it by 1000.

I looked straight down. Fields, forests, roads, whole neighborhoods—the bird’s eye view was surreal. I thought I might throw up my breakfast over it all.

A pair of hands jerked my head and eyes upward. “Keep looking at the horizon, Private,” the jumpmaster yelled. “Yes, Sergeant Airborne,” I replied, though as soon as he let go, my head dropped and I was again staring straight down.

He jerked my head up for the second time and when he let go, again my eyes and skull and helmet and whole fear-struck expression plummeted down to the earth’s surface. He and I went through this process three or four times before he gave up.

“Go Go Go!”

All in all, I was standing in the doorway for less than a minute before the light turned green. Proper execution of an airborne exit calls for an exaggerated kick out into the open skies rather than an actual jump.

However, when my world went green and the jumpmaster yelled “Go Go Go,” my lead leg did more of a knee-jerk shiver, like something you do during a checkup at a doctor’s office in reaction to a rubber hammer.

I have no idea if I closed my eyes or not, but I do know that I screamed my four-second count—the amount of time a paratrooper actually free falls before his or her chute opens—in a high-cry that could’ve landed me a spot as a soprano in an Italian opera.

(A commonplace airborne joke goes like so: “Every jump I’ve ever done was at night and into water. By which I mean, my eyes were closed and I pissed my pants.”)

Somewhere between seconds three and four, I felt an immense surge of energy pass through my risers, my harness, and the two legs straps that so conveniently run between my legs. If my voice wasn’t high when I first jumped, when my chute pulled, it definitely jumped a handful of octaves.

Though by the time I got out of the Army, almost four years to the day of my first jump, my record would show over twenty airborne operations, the immediate contrast between jumping/falling and floating never ceased to amaze.

Fort Benning isn’t known for its breathtaking views, but from twelve hundred feet in the air with a full range of motion to look in any direction, it might as well be paradise.

Not to mention the other hundreds of paratroopers falling down around me.

I really got the feeling that we were invading. Suspended in the air, I felt that I was part of something much bigger than myself.

The Army’s T-10 parachute isn’t designed to give a soldier much room in the way of direction control, so for the few minutes that I floated down, I really was just a passenger.

The descent feels slow, and there are moments when a gust of wind catches the chute and it feels like I actually started to go back up.

My training took over when I was eye level with the tall trees bordering the drop zone. I looked down and judged which direction I was falling (because, unless you’re in a vacuum, you never just fall straight down).

I decided more or less that I was heading to the right, so I reached up as I high as I could up my two left risers, pulled them to my chest, and attempted to level myself.

It worked, but only temporarily, because right before I hit the ground, my grip slipped and I let go of the risers causing me and my parachute to perform a very violent oscillation.

I went from watching the ground to staring up at the sun without turning my head.

Then I hit the ground, thigh, ribs, shoulder, and head all at once. But, I was alive, and I was overwhelmed with pride that I had successfully, though not prettily, fallen out of my first airplane.

$5 For A Slice, Shot, And PBR

Jumping out of airplanes was only part of my experience in the Army’s Basic Jump School, and really a small part at that.

Though the school had its moments of difficulty, for me, a soldier fresh out of basic training, the three-week course was a vacation.

I went from having zero freedom and every minute of my life dictated, to regular hours, nights and weekends off, and the option to go off base and enjoy the company of civilian minds over a few (or a few dozen) beers.

A group of guys from my platoon in basic training went through Airborne School at the same time as I did, and we soon developed a weekly routine during our stay.

Thursday nights were for wings at the local Hooters. Fridays, five or six of us would split the price of a single motel room, usually at the Howard Johnson or a Motel 6, before making our way to a corner pizza joint that had a daily special I’ll never forget: five dollars for a slice, a shot, and a PBR; and if that’s not a paratrooper’s last meal, I don’t know what is.

From there, we stumbled our way between any number of downtown bars and clubs where we would do our best to make up for lost time during sixteen sober weeks of basic training, until either no one was standing or every bar closed, and we could find a soft grassy spot to lie down and watch the calm waters of the Chattahoochee.

Columbus may not be most people’s idea of fun, but for me, at that time in my life, it was exactly what I needed.

“Balls of your feet! Calf! Thigh! Hip! Back!”

When not engaged in general tomfoolery or jumping out of planes, my days in Airborne School were focused on drills specific to one aspect of how to properly and safely jump out of a plane.

See, each week of jump school correlates to a certain phase. Phase one, ground week, where the highest altitude an airborne cadet gets to fall from is about five-or-so feet off the ground.

The point of Ground Week is to incessantly drill the infamous PLF, or Parachute Landing Fall (the Army’s capacity for coming up with creative names never ceases to amaze me).

Day after day, hour after hour, me and my fellow soldiers repeated the commands of the airborne cadre while touching the respective points of contact. “Balls of your feet! Calf! Thigh! Hip! Back!”

When done correctly, a PLF should look kind of like a cartwheel, only without hands. It is meant to absorb impact and reduce injury. While the method is surprisingly effective, it is also unsurprisingly difficult to do right after a live jump.

“Die Hard with a Vengeance!”

Phase one culminates in jumping out of a thirty-five-foot tower and zip-lining over a sandpit, which, trust me, is absolutely nothing like jumping out of a plane.

Phase two of Jump School is called Tower Week. In this phase, soldiers work up to jumping out of a two-hundred-and-fifty-foot tower and riding an impossibly steep zip line meant to mimic an actual jump.

In the summer of 2008, Fort Benning’s towers were out of commission for a reason that was beyond my pay grade, but I’ve heard they’re quite effective.

So, instead of Tower Week, my class simply repeated Ground Week, while adding in a few extra thirty-five-foot tower visits for good measure.

I could tell the airborne cadre were a little restless at the process of having to repeat week one, because, by the time of our tenth or jump low tower zip line, they were making us yell our favorite movie and name before zipping off. “Die Hard with a Vengeance!” I yelled, adding, “Private Piha!”

I waited for the customary pat on the rear end to signify my release from the tower, but it didn’t come. Reluctantly, I turned around. The cadre was smiling. “What in the hell kind of name is Piha, Private?”

“It’s Greek and Jewish, and also, I think, a little Spanish, Sergeant Airborne.”

The staff sergeant whose name I’ll never remember but whose mischievous grin I’ll never forget reached up and grabbed a rafter under the ceiling. “Yippie-Ki-Yay, Piha!” he yelled, before ingesting a swinging kick into my rear end and sending me flying out the tower and speeding down the steel cable.

Becoming A US Army Paratrooper

When I landed (“landed”) my first airborne jump, I realized with pride that I was well on my to becoming a US Army Paratrooper.

During Week three/Phase three, I would go on to jump four more times, thankfully not having to suffer the terror of once again being the first man out the door.

I don’t think I ever did a correct PLF, but I did get dragged across the ground when my parachute decided that it wasn’t finished catching a little wind, I got a mouth full of Georgia red clay when I came up with my own PLF routine: Balls of your feet! Knees! Face!

Still, at the end of the week, we marched to a parade field for our graduation ceremony, a little bruised up, but happily wearing our matte black jump wings pinned to our uniform.

But not everyone would make it. Jumping out of planes doesn’t come without a certain degree of risk.

On our fourth jump, a good friend of mine from basic training landed in a sitting down position, shattering his tailbone.

He wasn’t allowed to recycle into another class, nor graduate with ours though he was only one jump short, and before I knew it he received orders for a regular infantry unit at Fort Worth, Texas.

So, How Hard Is Army Airborne School?

I kind of hate to break it to anyone, but as far as Army Schools go, Airborne School is fairly easy.

Pass the physical fitness test and don’t get hurt, and the three weeks will fly by (no pun intended).

However, just passing Airborne School isn’t the end-all-be-all of becoming a paratrooper.

I found that the real challenge of being a paratrooper was living up the high standards of living and working in an Airborne unit.

These units, such as the infamous 82nd Airborne, the 173rd in Italy, or the 4-25 in Alaska (my unit), are very proud that they are not simply the regular infantry.

Airborne units may not conduct military jumps as much as the Army did in the past, but they still practice and maintain their airborne skills on a monthly basis, all so that, if the opportunity comes to jump into combat, every paratrooper will be prepared.

- Green Berets Vs. Rangers: 5 Major Differences - June 17, 2024

- Tattoo Policy For Each Branch Of The Military In 2023 - June 17, 2024

- Top 20 Reasons To Join The Military (and 7 Reasons NOT To) - June 17, 2024

Originally posted on January 7, 2019 @ 3:20 am

Affiliate Disclosure: This post may contain affiliate links. If you click and purchase, I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. I only recommend products I have personally vetted. Learn more.

I served as a United Stated Paratrooper with the 82nd Airborne from 85 to 90 and I loved the article. If I had read this article in June of 81, before leaving for “Benning School for Wayward Boys,” I would have said the author was out of his mind! “Easy.” However, having completed it, and having completed Ranger school, Jumpmaster School and a number of other courses I would agree. It was easy in comparison, but at the time it was a nightmare. I was just 18 and had no military experience other than 1 year or Army ROTC under my belt. The “Blackhats” were the closest thing to the Devil I had ever seen in my life and they knew it! Looking back I can laugh, but post Vietnam there were some scary NCO’s in that school. NCO’s that I would later help guide a young LT through his first year in Division. They weren’t quite as scary. Most of them anyways.

The best piece of advice 1st Sgt Baker gave use when we arrived at the school; “keep your mouth shut and your ears and eyes open!” “Stay alert and you will stay alive!” That is the best advice I have ever gotten in my life and I’ve followed it in everything I do.

The best piece of advice I got while at MOS training at Ft Devens, MA In 1984 was from a sergeant who was already serving with the 82nd at Ft Bragg. He told me to get ready for Airborne School well before leaving Devens. To run every day on my own, beyond the normal daily PT. To run as fast as I could and at least three additional miles each day. He also told me to work out at the gym daily and to max out on my pushups and sit-ups. So I did. It’s true The Black Hats will try to get in your face, to make you quit, especially on the first day of training, so being able to do many more pushups and sit-ups than required helps get past that hurdle. First week your thigh will take a serious bruising from repeat practice landings. That was painful, so I padded my thigh using extra tee shirts strapped to my leg with what else, duct tape. Believe me it works. The rest is just getting used to heights. Practicing jumping out in a harness attached to a cable during Tower Week at 30’ gets you past that “psychological barrier” humans naturally have to heights and then it’s fun to do. The intense summer heat and humidity in Georgia can be brutal, so try to start training in May if you can get that slot. They have cooling overhead sprays set up in the training areas for hot days and that does the trick. Keep your eyes on the prize. That First Jump is a blast. But so is the second, and the third, … So If you enjoy sports like skiing, and love the outdoors, chances are you will like Airborne School, too.